What Do You Do With 17 Million Tonnes of Soil and Stones?

A New Direction for Landfill Tax Reform

At the end of April, the Government launched its Consultation on Reform of Landfill Tax in England and Northern Ireland. The primary aim is to reduce the volume of materials going to landfill. A secondary, though no less important, goal is to eliminate incentives for Landfill Tax fraud.

Both aims are undoubtedly commendable. In fact, it may be fair to say they are of equal and interchangeable importance.

Current Landfill Tax Structure

Currently, there are two rates for non-hazardous landfill tax:

- £4.05 per tonne for inert, low-polluting materials such as crushed stone, sand or gravel (known as fines). The government notes these materials are often recyclable, reducing dependence on finite natural resources.

- £126.15 per tonne for non-inert, general waste.

The Government proposes gradually increasing the lower rate until it aligns with the standard rate by 2030.

The Financial Stakes

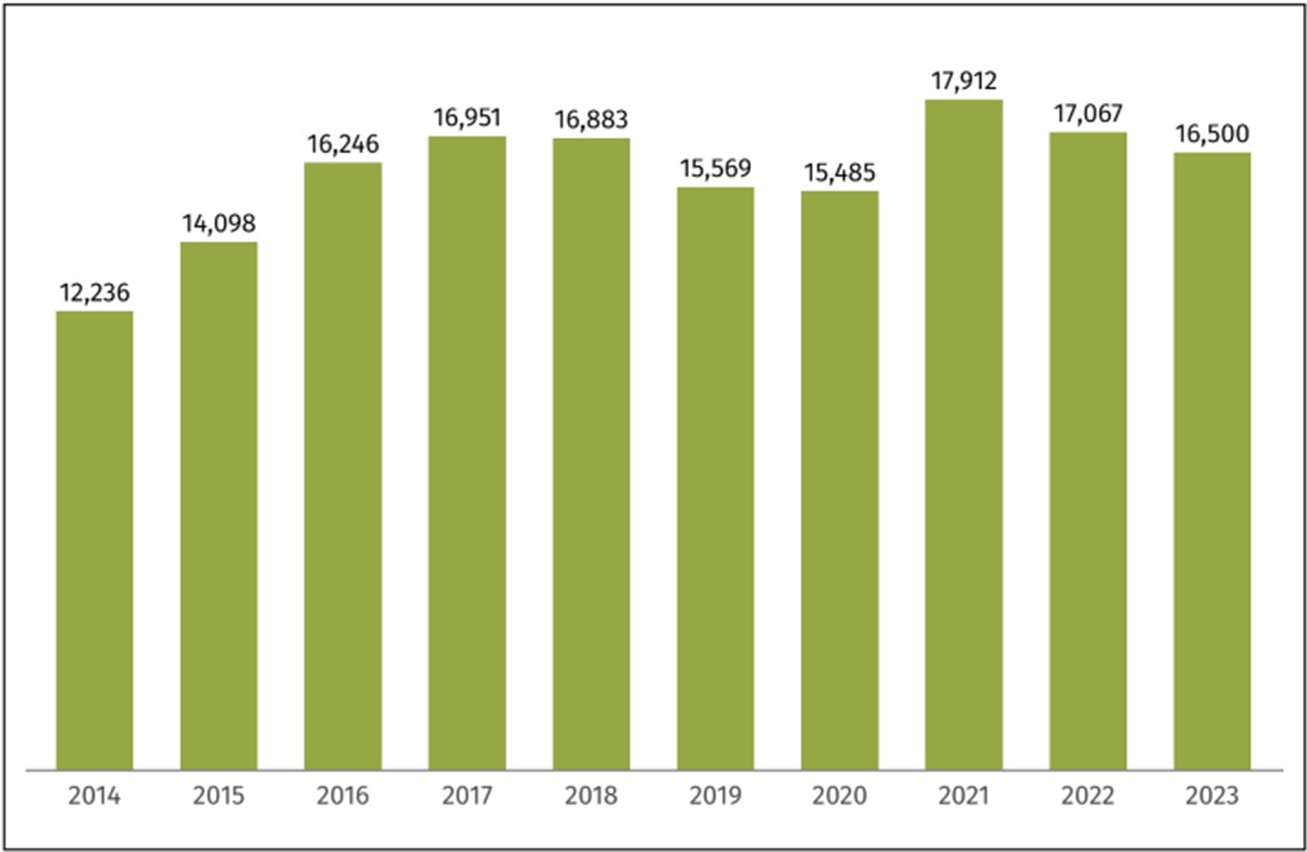

In 2023, nearly 17 million tonnes of qualifying material were sent to designated inert landfills in England (see Chart). Nearly 90% of this was categorised under EWC 17 05 04 (soil and stones).

Let’s do the maths:

- At £4.05 per tonne, these 17 million tonnes generate around £69 million in annual tax revenue.

- If taxed at the standard rate of £126.15 per tonne, the total would skyrocket to £2.1 billion.

An additional 8 million tonnes of soil and stones are disposed of in other landfills, often used as fill or daily cover to prevent lightweight debris from escaping in windy conditions. Applying the higher tax rate here too would bring in another £1 billion.

In total, that’s a potential £3 billion per year in revenue – just from soil and stones. A staggering 3,000% increase in tax.

Motivation or Misstep?

In financially constrained times, it’s hard not to wonder: is there a fiscal incentive driving this reform? £3 billion is a compelling motivator. But what are the broader consequences?

A Quarry Visit: A Case Study in Practicality

Several years ago, I visited a Yorkshire quarry producing paving blocks and slabs. The process involved water-cooled saws slicing stone into slabs. This created a rock-dust slurry, which was treated with flocculants, settled, and compressed into cakes.

The company, seeking advice, explained that the pressed slurry was being sent to landfill.

“My goodness!” I exclaimed. “We simply must do something about that!”

This was a moment of realisation. They were responsibly returning inert material to their own disused quarry voids, located nearby – minimising transport costs. These voids needed filling to avoid future safety hazards. What better material to use than inert rock-dust cake? Once filled, the land could be capped with topsoil and restored for nature or other uses.

Rethinking the ‘Landfill Is Bad’ Mantra

The widely accepted idea that “landfill is bad” is not always an absolute truth. As a strong supporter of the circular economy, I recognise the need to minimise harm to our planet and support biodiversity. But responsibly filling a quarry with inert material, then restoring the land, hardly seems environmentally damaging.

Increasing landfill tax on inert waste would impose unavoidable costs on companies like the paving block manufacturer. While it might push innovation to reuse slurry in new ways, it leaves a key question unanswered: What fills the quarry voids then?

Responsible Use of Inert Waste

Filling dangerous voids with inert waste is not a harmful act. It can be considered ethical and ecologically responsible – good land stewardship, even. Demonising this practice through punitive taxation is neither fair nor logical.

If fraud is the issue – where standard-rate waste is mixed with inert fines to reduce tax liability – then address it through stricter inspections, better testing, costlier penalties or smarter regulation. Blanket tax hikes will penalise compliant businesses, especially in construction, while failing to curb the actual problem.

The Risk of Unintended Consequences

Finally, if inert material is financially disincentivised from going to landfill, it will need to go somewhere. The most likely outcome? A rise in fly-tipping, on a massive and visible scale.

So, What Do You Do With 17 Million Tonnes?

What do you do with 17 million tonnes of soil and stones each year if you’re punished for using it to safely fill a hole in the ground?

That is the uncomfortable question this consultation must seriously consider.